A Carbon-based Wealth Tax for Climate Protection - Updated and Extended Proposal

Abstract | Wealth distribution and climate risks are two great challenges of our time. This paper proposes a new type of tax to correct wealth distribution and help finance (and accelerate) the green transition.

Jose Pedro Bastos Neves† and Willi Semmler†

October 13, 2024

Our proposal is a Carbon-based Wealth Tax (CWT) that should be levied on carbon-based (brown) wealth rather than carbon-intensive goods as the usual carbon tax would suggest which is often shown to be regressive. While the CWT re-corrects wealth distribution it raises revenue that could be used to subsidize the creation of green assets – by changing dynamic portfolio decisions and triggering a reallocation of assets from brown to green ones. To demonstrate those effects stylized green and brown asset returns using US data are calibrated as low-frequency returns on US assets between 2010 and 2021. We find that such a tax and subsidy scheme as designed by a CWT may not even adversely affect the wealth evolution. The CWT is a feasible, effective, and fairer instrument for reducing carbon emissions, and it supports a fair transition and control of sovereign debt dynamics.

∗The more technically oriented research paper on the Carbon-based Wealth Tax is available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4114243. Earlier versions of thispaper has been presented at the Henry George School of Social Science, June 2022 and the 26th Forum for Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (FMM) Conference, Berlin, Germany, in October 2022. This work has benefited from insightful comments from Katherine Pratt, David would like to express our special thanks to Joao Paulo Braga for advising us on the harmonic estimations. The paper was also presented at La Sapienza University, and at an EU Conference with participants from the EU Commission. Some of the research reported here is based on the book by Unra Nyambuu and Willi Semmler: Sustainable Macroeconomics. Climate Risks and Energy Transitions, Springer Publishing House, 2023. We want to thank for productive discussions Thomas Fischermann, Joao Braga, Juergen Zattler, Werner Roeger, Claudia Kemfert, Giacomo Corneo, Hans-Helmut Kotz, Michael Kuhn, Ibrahim Tahri, Stefan Mittnik, Timo Teraesvirta, and Dorothea Schaefer and colleagues at the IIASA, the New School for Social Research and the University of Bielefeld.

†Brazilian Ministry of Finance.

‡The New School for Social Research, NY, and IIASA, Laxenburg, Austria.

Introduction

In a recent article, Thomas Fischermann1 pointed out that until now, the debates on a tax on wealth or on the super-rich was justified from the perspective of the recognition of the increasing wealth disparity2 in many countries. In fact, it can be shown that the Gini Coefficient for wealth distribution in most of the advanced countries are worse than for income distribution. Indeed, there is plenty of academic theoretical and empirical work on this, early and prominently put forward by Thomas Piketty and his co-authors. But recently the debate turned to the issue whether some wealth of a small group of the super-rich could be used for supporting the transition to a low carbon economy.3

On the other hand, much academic work has shown that a carbon emission tax on economic activities or products (called carbon pricing), is a tax that needs to be very high to be effective but has quite adverse distributional consequences. There is usually a strong pass-through of a carbon emission tax to the buyers, for example, to the downstream producers and household consumers. Households with a high proportion of energy expenses in their budget are impacted most severely. Households with very high income are likely to cause much more CO2 emissions whereas lower income households pay a greater percentage of their income as carbon emission tax.4 In recent studies, efforts focused on directed technical change, such as invention innovation in renewable energy technology, seemed to be more effective, and faces less popular unrest against price increase when a carbon emission tax is used, see Chen and Semmler (2024). Although a price increase is felt by everybody, technology change is very sector specific and creates less general popular unrest. Nordic countries such as Finland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark seem to be more successful with the latter strategy, a technology-oriented strategy on decarbonization, see Chen and Semmler (2024).

Previous proposals to address wealth inequality

Traditionally, there have been made strong arguments against a capital or wealth tax 5 As to that point, there is now a widespread public discussion on the rise of wealth disparities around the globe.6 Proposals for correction of the rising wealth inequality are looming. It is well known that over some decades the wealth share of the top 5 percent of wealth owners, for example, are rising faster than the share of the rest of wealth owners, the former owning nowadays about 60 % or more of total wealth. Traditionally there were in Europe some policy measures against that – but with little success.

Traditionally European countries such as Norway, Spain, France, and Italy have a wealth tax on either personal wealth, or on certain types of assets, such as real estate. Spain has a 3 % of wealth tax and France a mixture of personal wealth tax and tax on specific assets, roughly 1 and a half to 2 %, the former is an individual wealth tax, the latter a solidarity tax (recently) and a real estate tax. In the US the plan by Elizabeth Warren was a wealth tax of 2 % for wealth over and above $50 million. Let us say an asset return (risk free rate plus equity premium) nowadays amounts roughly to 8 %, as Shiller has estimated historically. The remaining return would be in the case of Spain roughly 5 %, in France roughly 5 to 6 % and in the US 6 %. The before tax return are roughly used as an average with respect to the expected returns and deductions. For the very wealthy there is a positive feedback loop – the higher the wealth, the greater are the returns and the growth rates of wealth, due to information advantages, better collaterals for borrowing, higher saving rates, and greater research and management staff for generating returns.7 Therefore the actually received returns can be quite above the 8 percent and the actual tax payments are usually much less than 2 percent, and closer to zero; see Zucman, Interview, (2024) and Zucman (2024).

At first sight, a percentage of tax on the returns of wealth owners appear as some loss of returns. But as we will show total wealth evolution might not be affected much. As we can demonstrate, in a dynamic portfolio model, there might not even be a loss of asset accumulation in cases where we impose a CWT. As we will show below, the reduction of brown asset returns could be compensated by an increase of green assets and the wealth evolution might not decline faster, in fact it may even improve with a CWT.

Recent motivations and initiatives

Recent discussion went a step further connecting the wealth returns to climate change: "Tax the 3,000 richest people in the world!" demanded Nobel Prize-winning economist Esther Duflo at the IMF Spring Meeting in Washington. Surprisingly, she received enthusiastic support from a predominantly finance-minister audience from around the globe. Duflo, along with other influential economists like Gabriel Zucman and Thomas Piketty, advocate the above mentioned proposal.8 They propose a minimum tax on the assets of the world’s richest people — say, 2%. The revenue, which could amount to an extra $250 billion per year could be transferred to poorer countries to combat the effects of climate risks and finance and energy transition.

Brazil’s Finance Ministry is also very active in drawing proposals and advocating of such taxes, repeatedly raising the issue in international meetings. Brazil will host the G20 meeting in Rio de Janeiro in November and the World Climate Conference in Bel ́em in 2025, where this discussion is likely to continue.9 At previous G20 meetings, ministers from diverse countries like France, Spain, and South Africa have voiced their support for taxes on the super-rich. Even Germany’s Development Minister, Svenja Schulze, has also signed a declaration in favor of such measures. Taxes on the wealthy would indeed be extremely fair (and climate-friendly): as the richest one percent of humanity currently emits as many greenhouse gasses as the poorest two-thirds of the global population. The poor, however, are the first to suffer the consequences of climate change.

If such a tax were imposed, several practical questions would arise: Who would guarantee that the money collected would truly be used to combat climate change? And how could we prevent the age-old problem of the wealthy moving their capital to countries without such taxes? The proper answer is "tax harmonization"—that is, coordinated taxation across the main countries where the rich reside. Without such minimum harmonization, the new Brazilian proposal probably won’t work.

However, in our original paper (see Bastos and Semmler, 2022) we are introducing another approach. We draw on traditional public finance principle and some political traditions, well alive also in Brazil. The public finance principle since Wicksell and Lindahl is the proportionality principle: Those who enjoy more public goods should pay higher taxes, which can be reversed: those who produce more public “bads” (for example destruction of the environment and release of greater CO2 emission) should also pay more.

A new proposal – A carbon-based wealth tax

Our new proposal is driven by several motivations. A tax and subsidy scheme that corrects the deterioration of wealth distribution, is a feasible, effective and fairer instrument in speeding up the transition to a greener economy, and is helping to generate revenue for the public budget and control sovereign debt dynamics.10

Technically, our proposal of a wealth tax our CWT would not target the stock of assets, but the income derived from them, which we find less problematic. In this case, taxing income from carbon-based assets would have a similar effect to taxing the assets themselves but would be easier to implement. A wealth tax often presents many loopholes, whereas a tax on income from wealth and capital gains is typically easier and requires less information.

However, the biggest challenge lies elsewhere: How do you differentiate between “brown” and “green” capital? At first glance, this seems like an insurmountable problem. But recent advances have been made by economists in determining how much CO2 is emitted by different industries and companies. In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and in the EU, the European Commission, are working on disclosure requirements that will compel companies to report their CO2 emissions—supported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the OECD. This idea is based on academic research. Patrick Bolton of Columbia Business School is arguing that large corporations, and also ESG firms Environmental, Social, and Governance), should disclose their respective CO2 emissions. According to his findings, this data is relatively easy to obtain.

In our proposal to tax asset flows, the income from the brown assets, are roughly 30 % of the income from brown assets which can subsidize the green assets. The net return from wealth, would of course fall in different countries: the remaining return in the case of Spain, France and the US is roughly 5 %(if we assume a normal asset return). However, the return of the green assets at roughly 8% would be higher than those 5%, composed of risky and risk-free rates. These could be roughly 10 to 11% if subsidized. The green assets would be preferred in portfolio decisions, generating over time a higher proportion of green assets in dynamic portfolios and financially supporting the decarbonization efforts.

Though both the returns of green and brown assets are fluctuating over time, but the brown assets fluctuate much more. This is shown in figure 1 which is taken from Bastos and Semmler (2022). In that working paper we report harmonic estimations of returns on green and brown assets using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the time series (see also Chiarella et al. 2016). This way we can capture low frequency movements on the returns, eliminating short-term noises that are usually disregarded in low frequency portfolio decisions. What is used here are a sum of sine-cosine coefficients and the Sum of Squared Errors obtained from the harmonic estimations.

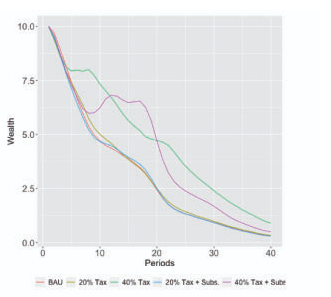

Figure 1 plots both estimations of the low-frequency behavior of green and brown assets. As can be observed and consistent with other findings, brown assets are more volatile. On the other hand, green returns are more resilient to economic swings. In Bastos and Semmler (2022) the dynamic portfolio optimization problem is solved numerically using the Nonlinear Model Predictive Control (NMPC) algorithms discussed in Gruene et al. (2015). We undertake a simulation for 40 periods for different tax regimes. In the Business-as-Usual (BAU) scenario, no tax is imposed. To evaluate the CWT’s impact, we run the model for before and after-tax brown returns and subsidies for green returns. We investigated scenarios with a rate of 20% and 40% as CWT and alternatively with subsidies to capture the influence of those magnitudes on the wealth trajectories. An intuitive explanation for the dynamic results in the simulations of figure 2 is: with those CWT the red line of figure 1 shifts down and with subsidies the green curve shifts up and substitution effects of green for brown assets set in. But there are more intricate mechanisms working.

Figure 1: Harmonic estimations of green and brown asset returns

Figure 2: Evolution of total wealth after taxation and subsidies; as observable we have chosen a parameterization of the model such that wealth will be depleted in finite time

Figure 2 depicts the wealth dynamics, which is presumed to decline over time (with consumption reducing it more than it can rebuild through returns). We observe the following three cases:

• For a 20 % tax of CWT with or without subsidies for green assets, the result is not much different than what we get for the BAU case (the case of “business as usual”, or no tax). In the 20% CWT tax case, wealth accumulation is not affected much but financial resources are shifted to decarbonization efforts and green assets, capturing the dynamic path. This means the red curve shifted down, and the green curve shifted up by certain percentages in figure 1.

• When the CWT is 40% on income from carbon-based wealth, meaning returns remaining roughly 5 % percent, assuming total average return of 8%, then the read line holds. There is now a greater wealth fraction of green assets, more

resources shifted to decarbonization and to green asset holdings. But overall the wealth is shrinking less than in the BAU case and previous cases.

• There is a surprising similar, but not very realistic case of preservation of wealth as in the last case, namely when there is a 40% CWT only and no subsidies for green wealth. Wealth preservation is then kept at a higher level as compared to the first cases, but this scenario presumes that there is a strong substitution effect from brown to green assets, so overall total wealth is better preserved.

Though there are some more delicate specifications behind our simulation results, the results of the scenarios appear reasonable. However, one of the major issues is how to distinguish between green and brown assets. We can call this the identification problem, which should not be a self-defined declaration of companies, but publicly evaluated and enforced.

The identification problem and policy reinforcements

To identify brown and green assets, there is an idea developed by researchers that is more specific for advanced countries: The specific idea is to impose a substantial new tax on the super-rich—but without treating all assets equally for publicly listed companies. A distinction could be easily made between "brown" and "green" assets: oil fields, mining, steel production, factories producing internal combustion engines, and other CO2-emitting industries, as well as coal and fossil-fuel based electricity production, on the one hand, and climate-friendly wind farms, solar energy firms and forest investments on the other. Income from "brown" assets could be taxed heavily—possibly at rates as high as 20% or more. The revenue generated would finance climate programs and could subsidize companies generating "green" assets. We thus have named this proposal the Carbon-based Wealth Tax (CWT) and the hope is that asset owners will shift from "brown" to "green" assets over time to optimize their tax burden.

As mentioned, technically, the tax would not target the stock of assets but the income derived from the assets, which is less problematic. In this case, taxing income from carbon-based assets would have a similar effect to taxing the assets themselves, but it would be easier to implement. A wealth tax often presents many loopholes, whereas a tax on income from capital is typically easier and requires less information. However, the biggest challenge lies elsewhere: How to differentiate between “brown” and “green” capital? At first glance, this seems like an insurmountable problem. But recent advances have been made by economists in determining how much CO2is emitted by different industries and companies.

This idea is partly based on academic research, with Patrick Bolton of Columbia Business School, who argues that large corporations, and also ESG firms (Environmental, Social, and Governance), should disclose their respective CO2 emissions. According to his findings, this data is relatively easy to obtain. In the U.S., the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and in the EU, the European Commission, are working on disclosure requirements that will compel companies to report their CO2 emissions—supported by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the OECD. Details of how the identification would be done can be found in Bastos and Semmler (2022).

Admittedly, the current proposal does not yet provide a comprehensive solution, as it assumes that all assets in which the rich invest are held by publicly listed companies that fall under some reporting requirements. There are also plenty of smaller, or less regulated companies in advanced, developing, and emerging markets that operate under significantly less transparency. In these cases, a sectoral distinction could be applied: Small firms, even those not publicly traded, could still be taxed based on the emissions associated with their respective sectors. As research continues, it may become easier to distinguish between "brown" and "green" firms, sectors, and investment portfolios, following the sectoral distinctions11, thus enabling the appropriate taxation of wealth investments.

Conclusions

Wealth dispersion is an eminent problem in many countries, but historically a tax on the stock of wealth has shown mixed results for countries that have enacted a wealth tax. On the other hand, we have rising climate risks and the scarcity of public funds for the mitigation of climate change and adaptation to climate risks. In our proposal, we attempted to bridge those two acute problems by proposing the CWT. This appears not only fair for the correction of wealth disparities, but can also provide effective finance for public budgets and helping to mitigate sovereign debt dynamics. Our CWT is not a penalty on productive enterprises and wealth that also takes care of the environment and climate risks, but rather on those types of wealth that produce welfare decreasing and destructive externalities.

Though a similar – but less fair – effect could also be generated by a carbon pricing of carbon intensive products, and public income could also be raised by carbon pricing, the revenue being used for the green transition. However, implementing the CWT could generate funds in a fairer way and one could direct them toward technical change, to support invention and innovation in renewable energy technology. This seems to be a more direct correction of externalities and seems to be more effective. This strategy faces also less popular unrest against price increase as compared to a carbon emission tax used, see Roy et al. (2024). As a price increase through a carbon tax on products is felt by everybody, technology changes, however, are very sector specific, creating less general populist unrest. Nordic countries such as Finland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark, which have also heavily funded the implementation of new energy technology by public subsidies. Those countries seem to be more successful with the latter strategy, see Roy et al. (2024). Funds for those new technologies can be raised by a CWT.

In our discussion with experts on those matters the question is often raised that our proposal might fit for the US but less so for European countries (like Germany, France, Italy and Spain) where a larger number of firms are not listed in the stock market, but are rather small or medium scale family firms. But in this case, the sectoral principle could be applied here where one knows in which sectors firms operate. Data on sectoral based CO2 emissions are well known and could be used for the distinction of brown and green assets. Going deeper into the standard industrial classifications, as input-output tables do12, may help to achieve this distinction.

References

[1] Bastos, J. and W. Semmler (2022), A Proposal for a Carbon Wealth Tax: Modelling, Empirics, and Policy; SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4114243.

[2] Bolton, P., and M. Kacperczyk (2021). Do investors care about carbon risk? Journal of Financial Economics.[3] Chappe, R., Semmler, W. Financial Market as Driver for Disparity in Wealth Accumulation—A Receding Horizon Approach. Comput Econ 54, 1231–1261 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-018-9870-1

[4] Chamley (1986). Optimal taxation of capital income in general equilibrium with infinite lives. Econometrica, 607–622.

[5] Chiarella, C., Semmler, W., Hsiao, C.-Y., & Mateane, L. (2016). Sustainable asset accumulation and dynamic portfolio decisions. Springer.

[6] Fischermann, T. (2024). DIE ZEIT, German news paper, no 38, September, 5.

[7] Guvenen, F., Kambourov, G., Kuruscu, B., Ocampo-Diaz, S., & Chen, D. (2019). Use it or lose it: Efficiency gains from wealth taxation (Tech. Rep.).National Bureau of Economic Research.

[8] Gruene, L., Semmler,W., & Stieler, M. (2015). Using nonlinear model predictive control for dynamic decision problems in economics. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 60, 112–133.

[9] Hinrichsen, D., & Krause, U. (1981). A substitution theorem for joint production models with disposal processes. In Operations Research Verfahren (Vol. 41, pp. 287–291).1981

[10] Judd, K. L. (1985). Redistributive taxation in a simple perfect foresight model. Journal of Public Economics, 28(1), 59–83.

[11] Kaenzig, D. (2021). The unequal economic consequences of carbon pricing (Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3786030).

[12] Musgrave, R. A. (1973). Public finance in theory and practice. McGraw-Hill Kogakusa.

[13] Nyambuu, N. and W. Semmler. (2023). Sustainable Macroeconomics, Climate Risks and Energy Transitions, Springer Publishing House.

[14] Parker, D. and W. Semmler (2024). Monetary Policy and the Evolution of Wealth Disparity: An Assessment Using US Survey of Consumer Finance Data. Computational Economics 11, March; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10614-024-10560-1

[15] Piketty, T. (2013). Capital in the 21st century. Cambridge, MA: President and Fellows, Harvard College.

[16] Roy, A., P. Chen and W. Semmler (2024). Carbon Tax versus Renewable Energy Innovation — A Dynamic Model and a Regime Switching CO-Integration VAR Preprint [17] Saez, E., and Stantcheva, S. (2018). A simpler theory of optimal capital taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 162, 120–142.

[18] Semmler, W. and P. Chen (2024). Energy Transition, Price-Quantity Market Interactions and Inflation – A Model-guided Study and CIVAR Empirics for the US, manuscript.

[19] Straub, L., and Werning, I. (2020). Positive long-run capital taxation: Chamley-Judd revisited. American Economic Review, 110(1), 86–119.

[20] Zucman, G. (2024), Coordinated minimum effective taxation standard for ultra-high-net-worth individuals, Commissioned by the Brazilian G20 Presidency, manuscript.

[21] Zucman, G. Interview, July 2024, Proposal of a tax on the super rich, for an interview on this proposal, see https://www.npr.org/2024/08/06/nx-s1-5064662/global-wealth-tax-g20-poverty-climate-changefollowing proposal, July 2024.

1See the German weekly newspaper DIE ZEIT, No 38, September 5, 2024.The English version can be found here: https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/insights-blog/a-carbon-based-wealth-tax-for-climate-protection-a-proposal

2See Parker and Semmler (2024)

3An Oxfam report from October 28, 2024 writes: The top 1 per cent wealthiest responsible for same amount of carbon emissions as bottom 66 per cent; see https://www.ctvnews.ca/climate-and-environment/top-1-per-cent-wealthiest-responsible-for-same-amount-of-carbon-emissions-as-bottom-66-per-cent-1.6652001#:

4See K ̈anzig (2022).

5Traditionally the economic literature has maintained that optimality conditions imply a zero rate for capital tax, otherwise employment would be hurt. However, there have been recent challenges to this result. The canonical models of Chamley (1986) and Judd (1985) showed that the steady-state optimal capital taxation is zero when the long-run capital supply is infinitely elastic. Recent developments have cast doubts on such results. Saez and Stantcheva (2018) show how incorporating wealth into the utility function produces heterogeneity in wealth (unrelated to heterogeneity in labor earnings), invalidating the zero-capital tax result. Straub and Werning (2020)proved that intertemporal elasticity below one is already sufficient to produce positive capital taxation. Guvenen et al. (2019), in turn, demonstrated that agents can extract different returns from the assets. This heterogeneity is enough to yield a rationale for wealth taxation since it penalizes the idleness of asset holder.

6See https://wid.world/.

7See Chappe and Semmler (2018).

8For a report on this proposal, see https://www.npr.org/2024/08/06/nx-s1-5064662/global-wealth-tax-g20-poverty-climate-change

9In Brazil, political packages are often designed to ensure that the rich do not oppose them. For example, President Lula da Silva’s famous anti-hunger programs, which lifted millions out of poverty, would not have been possible without the tacit acceptance of industrialists, large landowners, and mine operators.

10A fundamental rationale for a CWT can indeed derived from the public finance literature. The proportionality principle in taxation, revived by the work of Richard Musgrave (Musgrave, 1973), maintains that those who enjoy a higher proportion of public goods need to pay higher taxes. Viewed in reverse, this means that those who create a higher proportion of ”public bads” — meaning negative externalities— need to pay a higher tax. Brown capital locks the economy into an unsustainable path. In that sense, it can be thought of as a public bad. The idea of “public bads” is also related to the joint production system where there are non-zero disposal costs (Hinrichsen & Krause, 1981). In this case, the unwanted products – in our case, carbon emissions – entail a cost that is not acknowledged in the price system, making a strong case for taxation.

11In the US there are 430 sectors identifiable that can be ranked according to their carbon intensities, see Semmler and Chen (2024).