Are You Just Getting By? The Alarming Truth About Economic Insecurity in the US

ISSUE BRIEF

(463 KB)

Past research revealed 50 percent or more Americans are economically insecure, struggling to meet basic needs or plan for the future. Despite the staggering scale of the incidence of economic insecurity, researchers struggle to define and measure insecurity. This brief explores why current metrics fall short, reviews groundbreaking efforts to quantify economic insecurity, and highlights findings that reveal a clear, troubling trend: families across the U.S. are living with heightened financial uncertainty. An accurate measurement would allow policymakers to craft meaningful solutions that will help Americans not just survive—but thrive.

Key Findings

Scholars agree the reality of the economic life of typical individuals and families needs to be measured.

Despite common agreement that economic insecurity matters, there is no one established definition of economic insecurity. Instead, there are a variety of nuanced measurements.

Despite the array of different economic insecurity measures they almost all lead to a similar conclusion: economic insecurity is widespread in the US.

The pursuit of a quantitative measure of economic insecurity is valuable and important, but without incorporating surveys or qualitative assessments, numerical data alone fail to capture the lived experience of financial insecurity. It is essential to integrate these approaches to provide a more comprehensive understanding of economic insecurity.

Trends in American Economic Security

The Federal Reserve’s 2023 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking reveals 52 percent of U.S. residents report merely getting by, with no savings from the month prior to the survey. At the same time, only 33 percent indicate they are living comfortably according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2024.

A 2024 report from the Urban Institute, The True Cost of Economic Security (TCES), provides a comprehensive analysis of the resources required for families to fully participate in contemporary society. In contrast to traditional poverty measures, TCES seeks to quantify the gap between a household's actual living costs and its available resources. This index is particularly nuanced, as it incorporates factors such as family composition, geographic location, and demographic characteristics. The report's findings are striking, revealing that 52 percent of Americans live below the TCES threshold, with nearly 60 percent of children affected. These results highlight the need for targeted policy interventions. Policymakers can leverage the TCES framework to better direct resources to high-need areas, ultimately enhancing economic stability for vulnerable populations.

Both the Federal Reserve and the Urban Institute argue that conventional economic measures, such as poverty and inequality indices, fail to adequately capture critical aspects of well-being, including risk, uncertainty, and economic security. For instance, the official U.S. poverty rate in 2023 was 11.1 percent, yet this figure overlooks the broader issue of economic insecurity, which affects approximately 52 percent of Americans. A significant portion of the population, while not classified as officially poor, is nonetheless struggling to meet basic needs and is not thriving. Households in this precarious position often live paycheck to paycheck, with limited or no ability to save for retirement. Moreover, reliance on public and employer-sponsored retirement benefits—especially in an era of retrenching social safety nets—leaves many without sufficient savings to buffer against future economic shocks.

Hacker, Rehm, and Schlesinger (2013) identified economic insecurity as a defining feature of the post-1970 American economy. They have documented its worsening for much of the population. Stagnant wages amid rising productivity, along with growing income and wealth inequality, underlie this decline in economic security (Stiglitz, 2016). Latner (2019) adds factors such as weaker labor unions, shorter job contracts, casualized employment, and declining institutions like marriage. Hacker, Rehm, and Schlesinger highlight how risks once managed collectively through public programs or pooled private benefits, like defined-benefit pensions, now fall on workers and their families.

Widespread economic insecurity demands policymakers' attention. The 2024 U.S. election results should prompt deeper reflection on addressing this discontent. While the direct link between economic insecurity and voting behavior is unclear, economic discontent undeniably shapes political outcomes.

Definitions of Economic Insecurity

Economic insecurity has many definitions.

“The risk of economic loss faced by workers and households as they encounter the unpredictable events of social life” (Western et al, 2012).

“(The outcome) from the exposure of individuals, communities and countries to adverse events, and from their inability to cope with and recover from the costly consequences of those events” (UNDESA, 2008).

“The anxiety produced by a lack of economic safety, i.e. by an inability to obtain protection against subjectively significant potential economic losses” (Osberg, 1998).

“The psychologically mediated experience of inadequate protection against hardship-causing economic risks” (Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger, 2013).

Definitions of economic insecurity share a common element – measurement of economic loss and protection against such loss. The measures also rely on subjective feelings about “fear or anxiety or risk of future economic loss. ” Fear, risk and anxiety all refer to the anticipation of potential losses, rather than to the materialization of the losses.

Subjective well-being measures, namely surveys, provide a way to measure the psychological and forward-looking component in the definitions of economic insecurity. Surveys capture the sense of economic well-being of the typical resident, yet they have some shortcomings. First, individual perceptions are not comparable as different individuals are more or less averse to risk or more or less anxious about the future. Second, the forward-looking aspect in the definition is difficult to make operational. Observations about economic loss are only possible once they have materialized. This implies that we are not measuring the state of unease connected risk, but the actual economic loss experienced once the risk has materialized. This has led to the rise of measures of perceived security vis-à-vis measures of observed security.

Measures of perceived security focus on those aspects in the definition of economic insecurity that are subjective and forward-looking such as anxiety. Measures of observed security refer to and account for the materialization of the economic losses that were feared in the first place.

Measures of Perceived Security

Measures of perceived economic security include subjective measures of the economic risks individuals think they will encounter. Though people do a reasonably good job of forecasting the risks they will experience, the downside of using subjective measures prevents comparing economic security across time or across countries. Examples of datasets that use measures of perceived security are University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index, the Eu-Silc survey questionnaires (see Hacker, Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand, 2018) and the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED of the Federal Reserve Board).

Measures of Observed Security

Scholars also aim to measure economic insecurity with measures that identify a household’s buffers and probabilities of economic shocks. Two well-cited measures include the Economic Security Index by Hacker et. al (2018) and the Index of Economic Security (Osberg and Sharpe 2015), which is a component of their Index of Economic Well-being (IEWB).

Buffers are a pivotal element of economic security since most measures of economic insecurity aim to capture the degree of protection against shocks. Wealth is the key buffer against income volatility and declines. Losing income suddenly but having wealth does not constitute economic insecurity. Good measures of economic insecurity capture wealth and other buffers against hardship, including private and public forms of insurance. Economic support from family or friends is also a source of buffer.

Although these measures may appear straightforward to construct, there are significant complexities related to both the unit of analysis and the time frame considered. For example, one key question is whether economic insecurity should be measured at the household or individual level. Individual-level measures may be more appropriate for groups such as single parents, whose economic security is often determined by their own resources. However, for individuals embedded in strong kinship networks, economic insecurity may be mitigated by social buffers, even if they lack substantial personal wealth.

The time frame for analysis also presents challenges. Most income and wealth data are collected on an annual basis, which fails to capture the fluctuations in economic security that individuals or households may experience within a given year (see Osberg, 2015). Moreover, composite indexes that aim to capture multiple dimensions of economic insecurity require careful decisions about how to weight and aggregate the various components, further complicating the measurement process.

The Paradox of Measurement

The diverse approaches economists have employed to measure economic insecurity highlight the complexity of the task. However, not measuring economic insecurity due to the complexity of the task, would lead to what Merry and Wood (2015) term the "Paradox of Measurement" (see also Delamonica, 2023).

The paradox of measurement refers to a scenario in which to give visibility to something “it must be countable, but if it has not already been translated into commensurable and quantifiable terms, it is difficult to count and may remain un-noticed and uncounted” (Merry and Wood, 2015). We often focus on measuring what is easiest to quantify, such as income and savings, while neglecting other potentially more significant factors, such as the anxiety and lower well-being associated with financial insecurity, the inability to plan for the future, and disengagement from political participation. This oversight would implicitly suggest that these elements are less relevant, even though that is not the case. The "paradox of measurement" underscores the importance of capturing all dimensions of economic security, despite the challenges involved in measuring them.

Research utilizing surveys on economic insecurity has effectively captured the various dimensions of economic hardship experienced by Americans. The following section will examine key findings that have emerged from these surveys.

Hacker’s Survey of Economic Risk and Perceptions and Insecurity (SERPI) review.

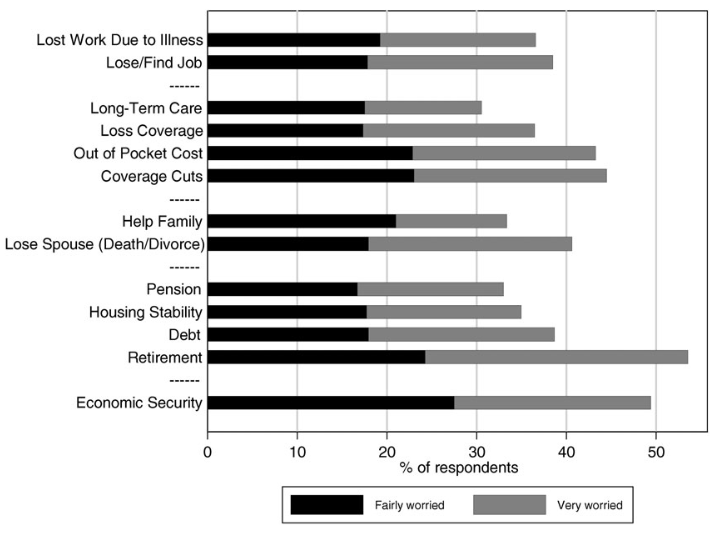

The SERPI by Hacker et al. (2013) illuminates interesting US empirics about economic insecurity. The SERPI is part of the Panel Survey of the ANES. Over 2,000 respondents between 2008–2009 were asked about their experience of economic disruptions and worries on four dimensions: employment, health, familial arrangements, and wealth. SEPRI also provides information on the actual buffers and capacity households have to self-insure against shocks and reduce the time to recover from those shocks. The table below displays some of the findings from the data collected concerning the dimensions that worry people the most. Around 40 to 50 percent of residents worry the most about old age and retirement security costs especially out-of-pocket health costs and health insurance coverage cuts.

Asking people about their subjective economic insecurity is not enough. Hacker and colleagues match these subjective worries with the actual materialization of the household experience. In doing so, they account for both the psychological dimension and the actual materialization of economic loss that define economic insecurity. They find anxiety exceeds the realization of the event. Worrying about not having enough saved wealth is an exception. Worries about adequate wealth and the actual experience of wealth shocks go hand in hand.

Figure 1: Scope of Worries

Source: Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger (2013)

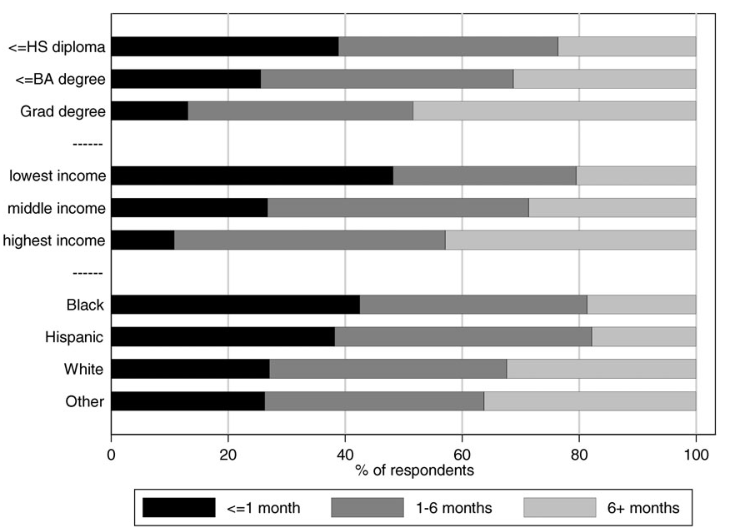

Hacker et al. find individuals’ capability to buffer – measured as the time households think it would take to recover from shocks -- differs by anticipated shock type and different demographic groups and among different segments of the population. People with higher levels of education are able to self-insure for longer (more than 6 months) compared to people with lower levels of edcuation. 50 percent of the residents with lower incomes are able to buffer for less than a month, compared to only 10 percent of residents of highest income that are able to buffer for the same time. Race and ethnicity also influence the ability to buffer. Around 45 percent of black people can buffer for a month or less compared to around 38 percent of hispanic people and around 25 percent for white and other races and ethnicities.

Figure 2: Ability to Buffer (by groups)

Source: Hacker, Rehm and Schlesinger (2013)

Conclusion:

In conclusion, I argue that while existing definitions of economic insecurity are adequate for understanding its various dimensions, the complexity and subjective nature of economic insecurity—especially the personal and psychological aspects—cannot be fully captured by a single index or formula. The most effective way to measure economic insecurity is through frequent, population-wide surveys. This approach offers a nuanced and dynamic picture of how individuals are truly faring, beyond what static measures like poverty or inequality can reveal.

The results from the two surveys presented in this paper highlight this point: despite differences in methodology, both surveys provide similar insights into the state of economic insecurity in the United States. This suggests that existing survey instruments are already capable of capturing the broad contours of economic insecurity, and should be conducted regularly to continuously monitor trends and shifts in people's economic well-being.

By prioritizing ongoing surveys, we can avoid the risks of overlooking important dimensions of economic insecurity, which often go unaddressed in traditional measures of poverty or inequality. The paradox of measurement underscores this challenge: while inequality is more easily quantified, economic insecurity remains harder to measure in its full complexity. This does not mean that inequality is inherently more important, but rather that it is easier to track and incorporate into policy debates. Regular surveys are the key to filling this gap, ensuring that we capture a more comprehensive and accurate picture of people's lived economic experiences.

References:

Acs, G., Dehry, I., Giannarelli, L. & Todd, M. (November 2024). Measuring the True Cost of Economic Security: What Does It Take to Thrive, Not Just Survive, in the US Today?, research report, Urban Institute

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board. (2024). Economic Well-being of US Households in 2023. https://doi.org/10.17016/8960

Delamonica, E. (2023). Measuring human rights? Vernacularisation and paradoxes of measurement in child poverty estimation. The International Journal of Human Rights, 27(7), 1154–1179. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2022.2153123

Ghilarducci, T., & James, T. (2018). Rescuing Retirement: A Plan to Guarantee Retirement Security for All Americans. Columbia University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/ghil18564

Ghilarducci, T. and Manickam, K. (2024). “How Americans Feel About Their Retirement Prospects: Surveying the Surveys.” Policy Note Series, Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research. New York, NY.

Ghilarducci, T., & Tursini, L. (2024). Americans' Downward Mobility Shifts Votes to the Right. Social Research: An International Quarterly 91(3), 795-818. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/sor.2024.a938578.

Hacker, Jacob S. et al. (2012): The economic security index: A new measure for research and policy analysis, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 6946, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn

Hacker, Jacob S., Philipp Rehm, and Mark Schlesinger. “The Insecure American: Economic Experiences, Financial Worries, and Policy Attitudes.” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 1 (2013): 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592712003647.

Latner J.P. “Economic insecurity and the distribution of income volatility in the United States.” Social Science Research, Volume 77, 2019, Pages 193-213, ISSN 0049-089X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.09.005.

Merry, S. E., & Wood, S. (2015). Quantification and the Paradox of Measurement: Translating Children’s Rights in Tanzania. Current Anthropology, 56(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1086/680439

Osberg, L. (2015), "How Should One Measure Economic Insecurity?", OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2015/01, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5js4t78q9lq7-en.

Osberg, L. (2018). "Economic insecurity: empirical findings," Chapters, in: Conchita D’Ambrosio (ed.), Handbook of Research on Economic and Social Well-Being, chapter 14, pages 316-338, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Nicholas Rohde & Kam Ki Tang, 2018. "Economic insecurity: theoretical approaches," Chapters, in: Conchita D’Ambrosio (ed.), Handbook of Research on Economic and Social Well-Being, chapter 13, pages 300-315, Edward Elgar Publishing.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2016). "How to Restore Equitable and Sustainable Economic Growth in the United States."American Economic Review, 106 (5): 43–47.DOI: 10.1257/aer.p20161006

Stiglitz, J., J. Fitoussi and M. Durand (eds.) (2018), For Good Measure: Advancing Research on Well-being Metrics Beyond GDP, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307278-en