Are Older Workers A New Reserve Army of Labor?

RELAB POLICY NOTE

(966 KB)

This policy note is part of SCEPA’s “Tracking the Retirement Crisis” series. This series was made possible in part through the generous support of The James Family Charitable Foundation and the Social Security Administration (RDRC23000009-01-00 and RDRC23000009-02-00). We are deeply grateful for their commitment to supporting our work and advancing research in this field.

Elevator Pitch: A growing pool of American older workers (age 55 and over) must continue working or seeking work because their retirement income is inadequate. The large number of older workers and the intensity of their financial need suggest this group could function as a “reserve army” of low-wage labor.1 The concept of a “reserve army of labor” – sometimes called precarious or buffer labor – is a large group of workers on the margins, ready to work, and easy to dismiss. A reserve army allows employers to adjust quickly to shifts in demand without raising wages or improving conditions in good times, or paying severance and layoff costs in bad. This reserve weakens the bargaining power of those already employed.

The “reserve-army-of-labor effect” likely varies by sector. Two occupations, janitors and home health and personal care aides, are particularly reliant on low-wage older labor. U.S. productivity and GDP growth is likely lower because many U.S. employers use older workers as a reserve army.

Older workers are working longer and the population is aging. According to the Department of Labor two million more older workers will enter the labor force in the decade 2024 – 2034 which is 38% of total projected labor force growth in the coming decade. 2 Older workers make up 24% of employment in 2025, up from a low around 12% in the early 90s. Notably before Social Security, pensions and Medicare kicked in, older workers were about 18% of the workforce. 3 The sheer magnitude of older workers’ means that what happens to them reverberates across the entire labor market.

Older Workers Work out of Necessity

Older Americans are working well past traditional retirement ages, either holding onto their jobs or re-entering the labor force after retirement or job loss.4 For many workers this decision is driven by inadequate retirement income.5 SCEPA and Boston College researchers found almost half of older workers are approaching retirement age without enough retirement income to maintain their preretirement standard of living or to stay above the poverty line.6

Another proof point for the reserve army dynamic is that displaced workers with long job tenure (who are more likely older ) accept large wage reductions (about 25%) if they change jobs after a period of not working. This is a sign many older workers may be working out of desperation.7

Hidden Unemployment of Older Workers Indicates Weaker Labor Markets

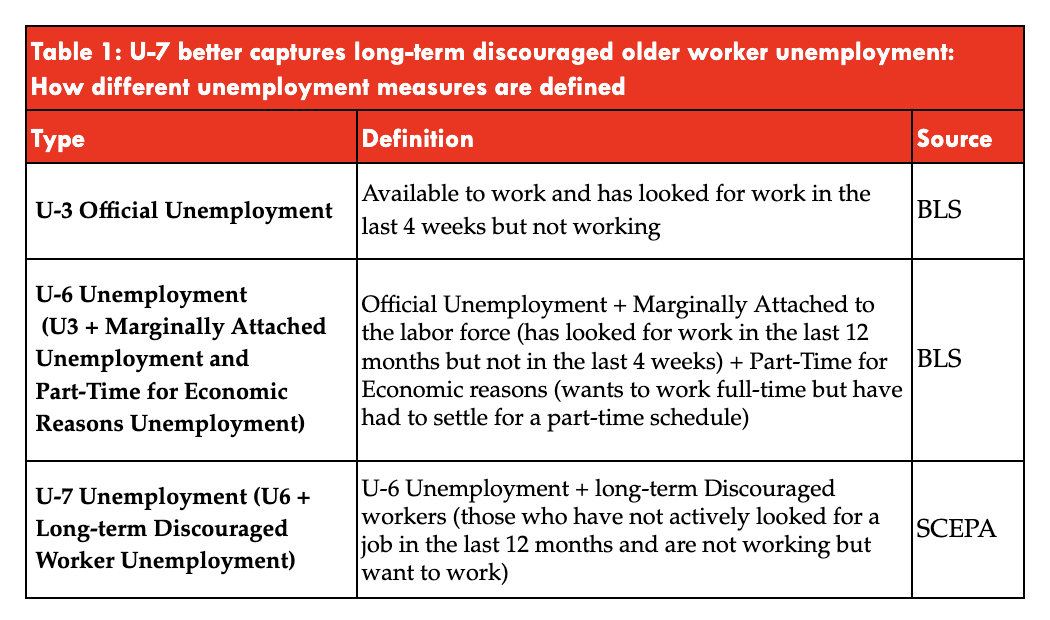

Older workers are a disproportionate share of the long-term unemployed. Every month the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports who wants a job and does not have one. The BLS publishes measures they label “U-1 through U-6”. U3 is the headline number – the rate reported on the first Friday of every month. Each unemployment measure includes one more group of people. U-6 is the most inclusive by adding people who work part time but want full time work and people who are “discouraged workers.” Discouraged workers are those who have not actively sought work in the last four weeks but have in the last 12 months.

Though U-6 is better than U-3 this expanded definition misses a lot of unemployed older workers. So, our research team constructed a “U-7” which is not an official BLS series. It is a Retirement Equity Lab/New School constructed index – a “New School U-7.” “U7” adds to U6 by including people who say they want a job, regardless of whether they have been actively seeking work.

In August 2025, more than one in five workers in U-7, 20.5%, were 55 or older, compared with 15.7% in U-3 and 16.8% in U-6. See Figure 1.

Many older workers are often missed in the official counts because when asked if they are working or looking for work the discouraged older person says, “I am retired.” Being retired feels more dignified than being discouraged or failing to find a job.

All these measures capture how many people want to work but do not have a job to one degree or another. When unemployment is high, employers can cut wages or not give raises, without losing workers. Unemployment, whether officially measured or hidden, suppresses wage demands and puts downward pressure on improving working conditions.8

Older workers are disproportionately represented in the broader measure of unemployment highlighting their vulnerability in the labor market.

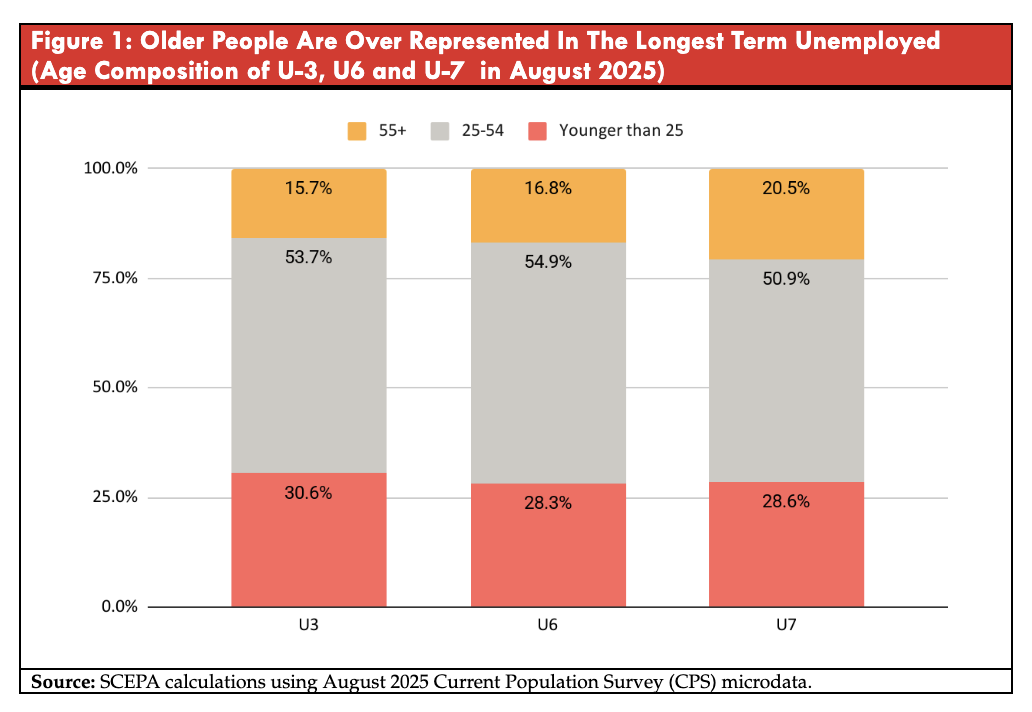

Older Workers Are No Longer Treasured By Employers

The older worker unemployment advantage got smaller after the PATCO strike,10 increased foreign trade11, and other legal and political changes that weakened union power.12 Unions bargain vigorously for job security measures, seniority clauses, retraining opportunities, and related protections.13 With a loss of these features, over time, older workers went from being “first in, last out” to, in some cases, “last in, first out.” As unions lost strength, older workers’ unemployment rates began to be closer to that of all workers.

How weak the older-worker-unemployment advantage is was apparent during the COVID recession. Older workers were hit first in the layoff wave – and instead of retiring directly, many spent time in unemployment. This break from the usual pattern was extraordinary: for the first time in nearly 50 years, older workers moved from layoffs into joblessness rather than quietly retiring.”14

This break with history underscores the insecurity that now defines older workers’ labor force participation – a hallmark characteristic of a reserve army of labor. Employers place less value on experience, and the premium for being older in the labor market has faded.15

Occupation Spotlight: Home Health and Personal Care Aides and Janitors

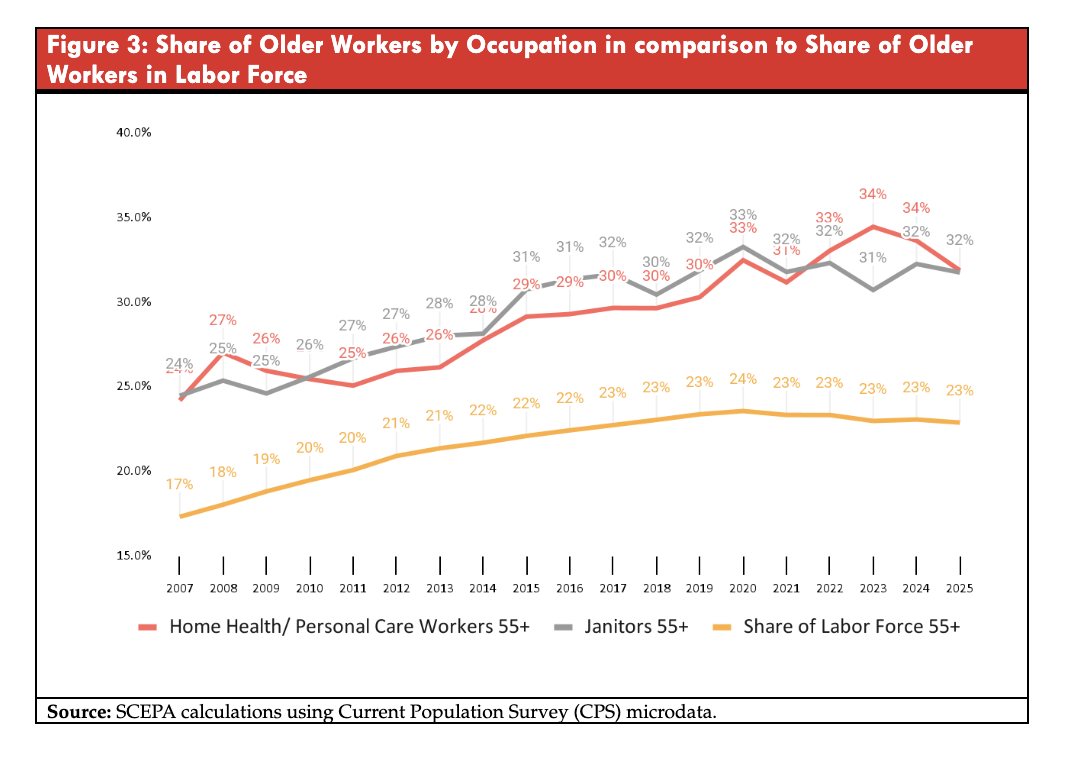

We spotlight two large occupations: home health and personal care aides and janitors. Employers of janitors and care workers hire more older people than the average employer in other sectors. According to SCEPA calculations using CPS microdata, in 2025, older workers made up 23% of the entire labor force but home health and personal care aides are disproportionately older, 32% are 55. And 87% of these care workers are women. Likewise, janitors are older – 32% of janitors are over 55, and about 68% of janitors are men.16

There are over 4.3 million home health and personal care aides and 2.4 million janitors, making them one of the largest and fastest-growing occupational categories. Janitors are also among the largest occupations by number of employed at more than 2.4 million. Both care workers and janitors are among the lowest paid. In 2025 janitor wages averaged $19 and the female-dominated care jobs paid an average of $18 per hour, while the national average wage was $27 per hour.17

Janitorial work and home health and personal care work involve heavy lifting and bending, tasks that do not get easier with age.18 These jobs are not attractive jobs with high pay or pleasant compensating differentials. These jobs do not seem to attract older workers so much as absorb them; these roles often look like jobs of last resort.

More than 6.7 million older workers are overrepresented in low-paid, difficult jobs, consistent with a “reserve army” dynamic.

See Figure 3

Above, we showed that U.S. unemployment is growing among older workers and growing in low-wage occupations suggesting a reserve army dynamic. We also showed how the labor market is aging. We close by discussing how a growing older worker reserve army might affect the macroeconomy, especially innovation, productivity, and economic growth.

An aging workforce in the United States corresponds to lower productivity because of the way American employers use older workers. In contrast,19 in Germany skilled workers (who are often older) train and mentor younger workers and impart firm-specific profitable skills.20 In Norway older workers boost productivity because, like in Germany, older workers train and mentor new and younger workers.21 When older American workers are pushed out or laid off from their longstanding jobs, their new jobs often pay much less and the new employer has little incentive to train or utilize all of their skills. Research shows that in the U.S., states with a faster aging workforce have lower productivity growth.22

Productivity doesn’t fall because of the American older workers’ traits. To be sure, physical strength, adaptability, and fluid cognitive ability on average decline with age, but age improves experience-based knowledge and crystallized cognitive ability.23 Since the bonds between employer and employee are relatively weak in the U.S., the American firm has less financial incentive to invest, train, and adopt new technologies when their workforce ages. In contrast to the German and Norwegian treatment of older workers, many American employers take a “burn and churn” approach rather than a “high-road” employment track of continual capital investment and keeping workers continually trained.24

Older workers could boost productivity and make better use of resources. That requires American employers and public policy to treat older workers as assets, not as reserve armies of labor.25

Policies to make Older Workers Stable and Valued Members of the Workforce

Policies that improve job quality and training for older workers, strengthen their bargaining power through adequate pension income and health insurance, and enforce anti-age-discrimination rules would help minimize the effect of older workers serving as a reserve army of labor.26

A key to raising the status of older workers is making them less desperate to accept any terms an employer offers. This can be achieved by increasing the quality and security of old-age income in the United States.

Social Security benefits need to be raised and protected from the automatic cutbacks which could come as early as 2031. That requires bringing in more revenue, which can be done by increasing the payroll tax base. 27

Rebuilding pensions with a universal pension savings program layered on top of Social Security would reduce older workers’ desperation.

Lowering the Medicare eligibility age to 60 and making it the primary payer for those aged 60–64 would reduce employers’ costs of hiring and retaining older workers. It could also reduce overall Medicare costs by ensuring that older workers—especially those who lose jobs before age 65—receive proper health care earlier, rather than entering the system at 65 with untreated conditions that could have been mitigated with proper care. 28

Conclusion

The evidence is clear: older workers are increasingly pushed into precarious jobs, weakening wage growth, bargaining power, and even long-term productivity. But this outcome is not inevitable.

With stronger Social Security, universal pensions, and earlier access to Medicare, older workers could have better jobs and more choice over whether to work or retire. These policies would not only restore dignity and security to older workers but also strengthen the overall labor market and economy. Ensuring that older workers are less desperate and more empowered must be a central goal of U.S. labor and retirement policy.

List of Figures

Figure 1: U-7 (55+) vs official U-6 (55+), monthly since 2007.

Figure 2: Ratio of Older unemployment to all unemployment

Figure 3: Age composition (55+ share) in Janitors and Home/Personal Care Aides, 2007–2024.

References

Goodhart, C., & Pradhan, M. (2020). The great demographic reversal: Ageing societies, waning inequality, and an inflation revival. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, August 28). Employment projections: 2024–2034 summary (Economic News Release USDL-25-1324). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.htm

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Level [CE16OV], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CE16OV, October 10, 2025.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2025, August). Labor force participation rate – 55 yrs & over [LNS11324230] [Data set]. FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS11324230

Morrissey, M., Radpour, S., & Schuster, B. (2023). Older Workers and Retirement Security: a Review. Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, The New School. Link

Ghilarducci, T., Papadopoulos, M., & Webb, A. (n.d.). “40% of Older Workers and Their Spouses Will Experience Downward Mobility in Retirement.”Ghilarducci, T., Papadopoulos, M., Fisher, B., & Webb, A. (2021). Working longer cannot solve the retirement income crisis (Policy Note Series). Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis. Link

Moore, B., Scott-Clayton, J., & Schaller, Z. (2023). The decline of U.S. labor unions: Import competition and NLRB elections. Labor Studies Journal, 48(1), 5–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160449X221126534

Kalecki, M. (1943). Political aspects of full employment. The Political Quarterly, 14(4), 322–331.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Unemployment rate – 55 yrs. & over [LNS14024230] [Data set]. FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LNS14024230

McCartin, J. A. (2011). Collision course: Ronald Reagan, the air traffic controllers, and the strike that changed America. Oxford University Press.

Schaller, Z. (2022). The Decline of U.S. Labor Unions: Import Competition and NLRB Elections. Labor Studies Journal, 48(1), 5–34. Link (Original work published 2023)

Shierholz, H., McNicholas, C., Poydock, M., & Sherer, J. (2024, January 23). Union membership data. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/union-membership-data/

Farber, H. S. (2021). Union decline in the United States: What do we know, what does it mean, and what can be done? Annual Review of Economics, 13, 355–382. Link

Retirement Equity Lab. (2022). Older worker bargaining power (Policy Note).Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis, The New School. PDF. SCEPA. (2020, October). A first in nearly 50 years: Older workers face higher unemployment than mid-career workers. The New School. Link

Farmand, A., & Ghilarducci, T. (2019). Why American older workers have lost bargaining power (Working Paper No. 2019-2). SCEPA.Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis & Department of Economics, The New School.

Wittenberg-Cox, A. (2023, October 27). Employers don’t care if you have 5 or 25 years experience: What to do. Forbes. Link

OECD/Generation: You Employed, Inc. (2023). The midcareer opportunity: Meeting the challenges of an ageing workforce. OECD Publishing. Link

Munnell, A. H., et al. (2020). Employer perceptions of older workers (Center for Retirement Research Report). Boston College.

Köber, C. (2001). Wage bias in worker displacement: How industrial restructuring reduces returns to seniority. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(4), 799–830.

Islam, A., Jedwab, R., Romer, P., & Pereira, D. (2019). Returns to experience and the sectoral allocation of labor (Working paper).SCEPA estimates using CPS Microdata.

SCEPA estimates using CPS Microdata

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Occupational employment and wage statistics: Janitors & cleaners (SOC 37-2011) and home health & personal care aides (SOC 31-1120). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/oes/

Goodhart, C., & Pradhan, M. (2020). The great demographic reversal: Ageing societies, waning inequality, and an inflation revival. Palgrave Macmillan.

Jäger, S., & Heining, J. (2022). How substitutable are workers? Evidence from worker deaths. (NBER Working Paper No. 30629). https://www.nber.org/papers/w30629

Hernæs, E., Kornstad, T., Markussen, S., & Røed, K. (2023). Ageing and labor productivity. Labour Economics, 82, 102347. Link

Ozimek, A., DeAntonio, D., & Zandi, M. (2018, September 4). Aging and the productivity puzzle. Moody’s Analytics. PDF

Sharpe, A. (2011). Is ageing a drag on productivity growth? International Productivity Monitor, 21, 82–101.

Skirbekk, V. (2008). Age and productivity capacity: Descriptions, causes and policy options. Ageing Horizons, 8, 4–12.Ozimek, A., DeAntonio, D., & Zandi, M. (2018, September 4). Aging and the productivity puzzle. Moody’s Analytics. https://ma.moodys.com/rs/961-KCJ-308/images/2018-09-04-Aging-and-the-Productivity-Puzzle.pdf

Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., & Powell, D. (2023). The effect of population aging on economic growth, the labor force, and productivity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 15(3), 1–37. Link

Neumark, D., & Song, J. (2013). Do stronger age discrimination laws make social security reforms more effective? Journal of Public Economics, 108, 1–16. Link

Board of Trustees. (2024). The 2024 annual report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. Social Security Administration. Link

Cubanski, J., Neuman, T., & Freed, M. (2019). The potential impact of lowering the Medicare eligibility age. Kaiser Family Foundation. Link

Suggested Citation: Ghilarducci, T. (2025). “Are Older Workers A New Reserve Army of Labor?.” Tracking the Retirement Crisis Policy Note Series. Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research. New York, NY.