America’s Retirement Crisis Hits a Breaking Point

RELAB POLICY NOTE

(858 KB)

This policy note is part of SCEPA’s “Tracking the Retirement Crisis” series. This series was made possible in part through the generous support of The James Family Charitable Foundation and the Social Security Administration (RDRC23000009-01-00 and RDRC23000009-02-00). We are deeply grateful for their commitment to supporting our work and advancing research in this field.

Elevator Pitch: Retirement security in the United States is at a critical turning point. As the Baby Boomer generation ages, the nation now has more retirement-age individuals—and more households relying on Social Security—than at any point in history. Yet the program is paying out more than it collects, and without legislative action, the Trust Fund will be depleted within a decade. Meanwhile, most private retirement savings have shifted to market-based accounts like 401(k)s, exposing near-retirees to financial volatility they cannot control. This dual vulnerability—an underfunded public system and risky private savings—demands urgent political action to secure promised Social Security benefits, strengthen the Social Security Administration, and pursue economic policies that safeguard household retirement wealth from avoidable market shocks.

Retirement security in the United States is entering its most precarious moment in decades. As part of SCEPA’s Tracking the Retirement Crisis series, this policy note highlights how shifting economic, demographic, and policy landscapes are reshaping the future of retirement for millions of American households. It examines the state of retirement security in the four decades since the last major reform to the U.S. retirement system—the 1983 Social Security Amendments. 1 Since that landmark legislation, sweeping demographic shifts, the projected depletion of the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, and the transition from defined benefit to defined contribution retirement plans have all undermined the stability of retirement income. To meet this historic challenge, bold legislative action and thoughtful governance will be needed to ensure Americans can retire with dignity and lasting financial security.

The Largest Retirement Age Generation in the United States

The United States is experiencing a historic demographic shift: more people are reaching retirement age today than at any point in the nation’s history. This shift is largely driven by the aging of the Baby Boomer generation—those born between 1946 and 1964—who began turning 60 in 2006 and continue to age into retirement in large numbers. Since 1983, the number of Americans aged 60 to 69 has grown dramatically (see Figure 1).2 From a relatively stable base ofaround 20 million people throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the size of this age group began to increase rapidly after 2005. By 2010, there were roughly 29.5 million Americans aged 60–69. That number surged to more than 40 million by 2023, and reached 40.8 million in 2024—more than doubling from levels just two decades earlier.

Figure 1: There Are More Retirement Age People in the United States Than Ever Before

Source: Census Bureau, Population and Housing Unit Estimates Datasets 2

Suggested Citation: Ghilarducci, T. (2025). “America’s Retirement Crisis Hits a Breaking Point.” Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research’s Tracking the Retirement Crisis Policy Note Series.

New York, NY.

This population shift has translated directly into a growing number of Americans claiming Social Security retirement benefits. The total number of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) benefi ciaries has increased steadily over the past four decades (see Figure 2). In 1983, there were about 32.2 million OASI beneficiaries. By 2003, that number had increased modestly to 39.4 million. But since then, the increase has accelerated: more than 60 million Americans now receive Social Security retirement benefits in 2024—a rise of over 20 million beneficiaries in just the last two decades.

This growth is not only a result of the Baby Boomer generation reaching retirement age, but also of increased life expectancy among some older Americans.3 While these gains have not been evenly distributed—and have recently stalled or reversed for some groups—longer lives mean that many retirees must draw benefits over more years than previous generations.4 For Social Security, this demographic reality presents growing administrative challenges: not only are more Americans entering retirement each year, but many will require continued support to navigate and maintain their benefits over time.

Figure 2: More Than 60 Million People Today Receive Social Security

Source: Social Security Beneficiary Statistics 5

Depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund

The Social Security Trust Fund is approaching a historic inflection point: unless Congress acts, the program will be unable to pay full promised benefits to retirees within the next decade. This looming shortfall is not just a future concern—it is the consequence of demographic and economic trends set in motion decades ago, and now converging in real time. The trajectory of the Trust Fund, from surplus accumulation to projected depletion, reveals the origins and consequences of the current funding crisis (see Figure 3). In the early 1980s, Social Security faced a short-term financing crisis not unlike today. In response, Congress passed the 1983 Social Security Amendments, which gradually increased the full retirement age, raised payroll taxes, and taxed benefits for higher-income retirees.6 These changes were explicitly designed to pre-fund the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation, whose aging had long been anticipated. As a result, the Social Security Trust Fund began to accumulate large surpluses, growing significantly from the mid-1980s through the early 2000s.Figure 3: Without Intervention The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund will be Depleted in the Next Ten Years

Note: Grey area represents future projections under an intermediate cost scenario Source: Historic numbers from Social Security Trust Fund Data.7 Future projections from Social Security’s 2024 OASDI Trustees Report 8

However, that upward trend ended in 2010, when Social Security’s annual cost began exceeding its non-interest income. Since then, the program has relied on drawing down its trust fund reserves to cover the growing gap between benefits paid and payroll tax revenues. The annual cost exceeded total income (including interest) starting in 2021, marking the point at which the Trust Fund began shrinking in absolute terms.

According to the 2024 OASDI Trustees Report, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund is projected to be depleted by 2033 under the intermediate cost scenario.8 At that point, without new legislation, Social Security will be legally allowed to pay out only what it collects in payroll taxes. That would result in an immediate 21 percent cut to all benefits, reducing payments to 79 percent of scheduled amounts.

The high-cost projection scenario, which assumes slower economic growth, lower fertility, and more rapid mortality improvement, pushes the depletion date even earlier—to 2032, and possibly as soon as 2031. This dynamic nature of depletion projections highlights the sensitivity of the program to macroeconomic and demographic shifts (See Box 1). The wide range of potential depletion dates—and the many variables that influence them—underscores just how volatile and precarious the outlook is for current and future retirees who depend on Social Security for stable income. Importantly, this depletion would trigger across-the-board cuts to all retirees, regardless of income or need. Unlike other budget programs that can prioritize or means-test benefits, Social Security operates under a pay-as-you-go structure that mandates uniform proportional payouts if trust reserves are insufficient.

Factors That Speed Up the Depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund

● Lower birth rates, reducing future payroll tax contributions● Higher unemployment, reducing worker contributions in the short term

● Lower real wage, weakening revenue

● Lower interest rates, reducing investment returns

● Higher disability incidence, increasing expenditures

● Increases in longevity, extending benefit durations

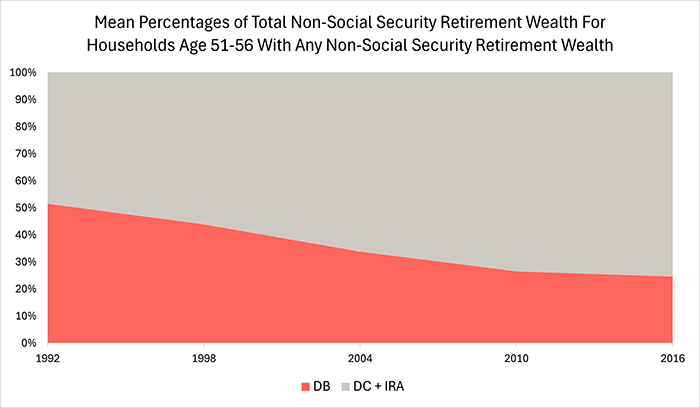

Today’s Retirement Assets Are Subject to Market Volatility Like Never Before

Over the past four decades, the structure of American retirement savings has shifted dramatically. While many households today have little or no retirement savings, those who do have savings are far more likely to hold them in defined contribution (DC) plans rather than traditional defined benefit (DB) pensions.9 10 Employer-sponsored DB pensions—once the backbone of retirement income—have steadily declined, replaced by DC plans such as 401(k)s and individual retirement accounts (IRAs).11 This transition has left individuals increasingly responsible for managing their own retirement investments and more exposed to the risks of financial market volatility.Data from the Health and Retirement Study show a striking transformation in the composition of retirement wealth, as households have shifted toward riskier asset holdings over the past three decades (see Figure 4 and Appendix for calculation details). In 1992, defined benefit plans on average accounted for more than 50 percent of total non-Social Security retirement wealth of households age 51-56 who had some non-Social Security retirement wealth. By 2022, the average share of secure defined benefit pension wealth had fallen to 25 percent. Meanwhile, riskier defined contribution and IRA assets have surged, together representing the majority of retirement wealth. Unlike traditional pensions, these accounts do not promise a predictable monthly benefit. Instead, retirement outcomes depend on individual investment decisions and the uncertainty of financial markets.

Figure 4: Market-Affected Assets Now Make Up the Majority of Average Retirement Wealth

Note: See appendix for calculation details

Source: SCEPA calculations from Health and Retirement Study 1992, 1998, 2024, 2010, and 2016 data.

Defined benefit plans offer a guaranteed stream of income in retirement, usually based on a formula that includes years of service and average salary. These plans typically provide lifetime annuity payments, reducing uncertainty about retirement income levels—something DC plans generally do not guarantee. This structure insulates workers from risks such as poor investment returns or outliving their savings. Under a DB plan, it is the employer—not the individual—who bears the responsibility for funding and managing investments. If more workers today had access to DB pensions, they would be significantly less exposed to market downturns, and their ability to retire would not depend on the performance of a 401(k) balance or stock portfolio.

12

Common retirement investments like Vanguard’s Total Stock Market Index Fund have experienced huge year-over-year changes, subject to the ups and downs of the broader economy (See Figure 5). Households approaching retirement age, with little time to recover losses, are particularly vulnerable. This exposure became painfully evident during the 2008 financial crisis. Stock and housing market crashes wiped out trillions in household wealth, forcing many older workers to reconsider their retirement plans. 13

Figure 5: Retirement Savings Held in Market Traded Accounts Can Vary Widely Year to Year

Source: Yahoo Finance, Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF Shares (VTI)

The Uneven Consequences of the Great Recession on Retirement

A growing body of research has documented the long-term consequences of the Great Recession on retirement security. An analysis published in the American Economic Review found that older adults responded to wealth losses during the crisis by delaying retirement—on average by more than two months for the typical wealth loss—particularly among those pessimistic about future market returns.

14

Another analysis published in the same journal reported that between 2006 and 2008, the expected probability of working at age 62 increased by 7 percentage points, reflecting widespread reassessment of retirement timing as asset values declined.

15

The effects were not uniform across the population. Higher-income households with greater market exposure delayed retirement to recoup investment losses. But for many lower-income and less-educated workers, the recession accelerated retirement due to job loss and limited re-employment opportunities.

16

For these workers, the crisis delivered a double blow: just as their already modest retirement savings were diminished by market declines, they also lost access to employment income that might have helped them recover. The result was an uneven impact: some delayed retirement to rebuild savings, while others exited the workforce early with inadequate resources.

Many households tapped into their retirement savings early. One research paper by three federal economists documents a significant rise in pre-retirement withdrawals during and after the Great Recession, particularly among those experiencing a loss of income or divorce. 17 While such withdrawals can provide short-term relief, they diminish long-term retirement security and reflect a broader system unable to cushion households against economic downturns.

As risky defined contribution plans continue to dominate the retirement landscape, policymakers must grapple with the systemic consequences of a savings-based system that fluctuates with each market cycle. For today’s near-retirees, the stakes of market downturns are higher than ever before.

Fixes Require Immediate Policy Action

The demographic pressures of an aging population, the projected depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund, and the volatility of individual retirement savings all point to the need for immediate, substantive policy action. Without timely intervention, Social Security will no longer be able to pay out full promised benefits—a scenario that would amount to an across-the-board benefit cut for millions of retirees, including the most vulnerable. Policymakers must act now to prevent this crisis.At the top of the agenda should be ensuring that Social Security is fully funded to meet all of its obligations. This means Congress must take steps to raise adequate revenue, such as lifting the payroll tax cap and increasing payroll contributions, as recommended in SCEPA’s prior work. Delays in action only raise the cost of eventual fixes: if reforms are postponed until the Trust Fund is exhausted, larger tax increases or deeper cuts will be necessary to restore balance .11

Preserving trust in Social Security also requires protecting the capacity of the Social Security Administration (SSA) itself. Over the past decade, Congress and the President have undermined Social Security through staffing cuts, planned field office closures, and politicized narratives that downplay its importance. As SCEPA’s recent policy brief warns, these actions threaten not just the SSA’s effectiveness but the well-being of millions of beneficiaries who rely on it for timely, accurate payments.

To ensure Social Security can meet its long-term obligations and serve the growing number of beneficiaries, Congress and the President must take the following steps:

● Raise revenue for Social Security to allow Social Security to meet and expand its obligations

● Reverse layoffs and restore SSA staffing to meet growing demand.

● Cancel planned SSA office closures and modernize infrastructure carefully and securely.

● Rebuild public trust in the system by maintaining stable operations, clear communications, and professional stewardship .

The political landscape also poses risks to retirement security. President Trump has suggested that a recession could be an acceptable cost of pursuing an aggressive trade policy.18 During a recent interview with ABC News’ “Meet the Press”, when asked about potential economic trouble, President Trump said everything would be “OK” in the long term even if the U.S experienced a short-term recession. 19 But even short recessions have lasting consequences for workers near retirement. As the experience of the Great Recession showed, economic downturns lead to job loss, depletion of savings, forced early retirement for some, and delayed retirements for others. Policies that flirt with triggering recession—intentionally or negligently—risk recreating the very conditions that imperiled a generation of near-retirees in 2008. It is critical that leaders prioritize economic stability over political theater.

Social Security has never missed a payment in nearly 90 years. It is not only a financial program, but also a promise—an intergenerational commitment that must be honored. Protecting and strengthening Social Security is not just good policy; it is a moral imperative.

Appendix

HRS retirement wealth calculations: HRS estimates are weighted for households with at least one person age 51-56. DB and DC pension wealth estimates are for the current job and are derived from the HRS Pension files for 1992 and 1998, 2004, 2010, and 2016. IRA wealth is taken from the RAND HRS Longitudinal File.

References

1. Social Security. Historical Background and Development of Social Security. https://www.ssa.gov/history/law.html Accessed: May 4, 2025.

2. Census Bureau, Population and Housing Unit Estimates Datasets. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/data-sets.html Access May 1, 2025.

3. Reznik, G. L., Couch, K. A., Tamborini, C. R., & Iams, H. M. (2021). Changing longevity, social security retirement benefits, and potential adjustments. Social Security Bulletin, 81, 19.

4. Auerbach, A. J., Charles, K. K., Coile, C. C., Gale, W., Goldman, D., Lee, R., … & Weil, D. N. (2017). How the growing gap in life expectancy may affect retirement benefits and reforms. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance-Issues and Practice, 42(3), 475-499.

5. Social Security. Social Security Beneficiary Statistics. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/OASDIbenies.html Accessed: June 28, 2025.

6. Social Security. SUMMARY of P.L. 98-21, (H.R. 1900) Social Security Amendments of 1983-Signed on April 20, 1983. https://www.ssa.gov/history/1983amend.html Accessed: May 4, 2025.

7. Social Security. Trust Fund Data. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4a3.html Accessed: June 28, 2025.

8. Social Security. (2024). The 2024 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds. https://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2024/ Accessed: May 4, 2025.

9. Phillips, D., Ghilarducci,, T., & Manickam, K. (2025). Retirement then and now: Shortfalls in the retirement system will fail many future American retirees. Journal of Retirement, 12(3). https://doi.org/10.3905/jor.2025.1.175

10. Ghilarducci, T., Radpour, S., & Forden, J. (2024). No Rest for the Weary: Measuring the Changing Distribution of Retirement Wealth in the United States. Review of Political Economy, 36(2), 461-480.

11. Gale, W. G., John, D. C., & Iwry, J. M. (2024). SECURE 2.0 and the past and future of the US retirement system. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/secure-2-0-and-the-past-and-future-of-the-us-retirement-system/

12. Doonan, D. & Boivie, I. (2025). Pensionomics 2025: Measuring the Economic Impact of Defined Benefit Pension Expenditures. The National Institute on Retirement Security. https://www.nirsonline.org/reports/pensionomics2025/

13. U.S. House of Representatives, Oral Testimony. Committee on Education and Labor. "The Impact of the Financial Crisis on Workers' Retirement Security." 1:00, 2181 Rayburn House Office Building. Tuesday October 7, 2008.

14. McFall, B. H. (2011). Crash and Wait? The Impact of the Great Recession on the Retirement Plans of Older Americans. American Economic Review, 101(3), 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.40

15. Goda, G. S., Shoven, J. B., & Slavov, S. N. (2011). What Explains Changes in Retirement Plans during the Great Recession? American Economic Review, 101(3), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.29

16. Coile, C. C., & Levine, P. B. (2011). The market crash and mass layoffs: How the current economic crisis may affect retirement. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 11(1).

17. Argento, R., Bryant, V. L., & Sabelhaus, J. (2015). EARLY WITHDRAWALS FROM RETIREMENT ACCOUNTS DURING THE GREAT RECESSION. Contemporary Economic Policy, 33(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12064

18. Sanger, D. (2025). A Flashing Economic Warning and a Sharp Political Jolt. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/30/us/politics/trump-first-quarter-economic-reports.html Accessed: May 4, 2025.

19. NBC News. (2025). Trump downplays recession fears, saying the U.S. would be 'OK' in the long term. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/trump-administration/trump-downplays-recession-fears-saying-us-ok-long-term-rcna203511