Cuts to Medicaid Put Older Americans and Their Families at Risk

RELAB POLICY NOTE

(849 KB)

This policy note is part of SCEPA’s “Tracking the Retirement Crisis” series. This series was made possible in part through the generous support of The James Family Charitable Foundation and the Social Security Administration (RDRC23000009-01-00 and RDRC23000009-02-00). We are deeply grateful for their commitment to supporting our work and advancing research in this field.

Elevator Pitch: Over 5 million older Americans and adults with disabilities rely on Medicaid for long-term care services.1 Sweeping federal budget cuts passed in July 2025 in a partisan reconciliation bill (OBBB) threaten to weaken their care support. Reduced funding, new work requirements, and added administrative barriers to enroll will drastically limit their access to care. The care burden will likely shift to unpaid family caregivers already stretched to their limits. This Retirement Tracker breaks down the consequences Medicaid cuts will have on long-term care for older Americans.

Cuts to Medicaid Put Older Americans and Their Families at Risk

The “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) cut Medicaid by adding work requirements, complicating eligibility and renewal, and reducing the Medicaid provider tax. The cuts are projected to reduce spending by $911 billion over 10 years, and weaken health coverage and service quality.2 Although these changes won’t begin until late 20263(after the midterm national elections), we know these cuts will hurt older Americans receiving long-term care through Medicaid and the families that support them.

Family caregivers are overwhelmed and most cannot afford the cost of long-term care. The national median costs of home care in 2024 exceeded $75,000 a year, while nursing home care costs over $111,000 annually.4 Over half of Americans will need long-term services and supports (LTSS) at some point and many of those adults will need support from a family member to meet their care needs.5 In 2025, an estimated 59 million Americans were caregivers to an adult, with over 40% of those caregivers performing high-intensity care.6

American families provide unpaid care and arrange services to ensure that their loved ones receive the care they need to age with dignity. In 2021, Medicaid funding accounted for 44.3% of long-term services and supports (LTSS) payments, amounting to $207 billion.7 Gutting Medicaid will place further strain on families already overburdened and leave some elders without care at all.

Suggested Citation: Ghilarducci, T. (2025). “Medicaid Cuts Shift Long-Term Care Costs to Families.” Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research’s Tracking the Retirement Crisis Policy Note Series. New York, NY.

Eligible Adults Will Lose Coverage as Administrative Burdens Increase

The OBBBA reduces Medicaid spending by implementing new work requirements and complicating existing eligibility and renewal processes. The new rules will cause some eligible adults to lose Medicaid coverage due to complex administrative processes.

Adults aged 19-64 will now have to prove that they are working, volunteering, or in school for at least 80 hours per month. However, over 2.5 million adults below the age of 65 need long-term care support and cannot work the required hours.8

Long-term care is often considered an issue primarily for adults aged 65 and older. However, in 2022, nearly 4.8 million adults aged 50-64 received health coverage from Medicaid. 1.6 million of those adults had some functional limitations, like difficulty getting in and out of bed or using the bathroom (See Figure 1).9 While adults aged 65 and older on Medicaid also likely have Medicare coverage, Medicare does not cover long-term care services. Losses in Medicaid coverage mean losses in long-term care services for elders regardless of Medicare access.

Figure 1: Nearly 1.6 million Medicaid Covered Older Adults Have Difficulty with Daily Activities

Source: SCEPA calculations using 2022 Health and Retirement Study. The sample includes adults aged 50 and older. Having functional limitations is defined as having difficulty with one or more activities of daily living.

Exemptions for caregivers and individuals who are medically frail aim to ease the effects of work requirements for some older adults.10 However, past experiences with Medicaid work requirements demonstrate that even some individuals who would be exempt under the new requirements will lose coverage.11

Medicaid work requirements reduce health coverage without increasing employment. In 2018, Arkansas became the first state to implement work requirements for Medicaid recipients.12 The new requirements led to the disenrollment of 18,000 people before a 2019 court ruling halted further implementation. Coverage was reinstated for most of the disenrolled, many of whom were eligible under the struck down work requirements.13

Work requirements increase the administrative burden on individuals to prove their eligibility or their exemption. But the OBBB goes further. It doubles the frequency of eligibility checks and rolls back federal rules that simplified enrollment and renewal.14Individuals will now have to prove their eligibility twice a year instead of annually. Those who received Medicaid coverage through the Affordable Care Act expansion will lose their auto-renewal.15

These changes will make Medicaid enrollment and renewal harder for everyone, especially adults with functional or cognitive impairments, who may struggle to complete paperwork or navigate complex systems. The burden will instead fall to family members, who will now face more bureaucratic hurdles to keep loved ones covered. Without the help of family members, these adults may lose their benefits.

Greater administrative burdens will increase workloads for Medicaid staff. Medicaid offices will likely struggle to meet the new requirements and frequency of eligibility checks in an environment where most offices are already understaffed.16 The OBBB Medicaid cuts are part of a larger Trump-era trend: defunding public programs while weakening the agencies meant to deliver them – just as we’ve seen with the Social Security Administration.

Medicaid Cuts Will Reduce Home Care Options Forcing Difficult Choices

Funding cuts to Medicaid will also likely impact the types of long-term services and supports (LTSS) states cover. Under the OBBB, the Medicaid provider tax rate cap is lowered, which will reduce federal funding for state Medicaid programs.17 With less federal funding, states will seek to cut Medicaid spending. Not all states will be impacted to the same degree though, with Louisiana, Illinois, Nevada, and Oregon projected to see the biggest impacts with 19% or greater cuts.18

Under Medicaid some long-term care services, like institutional care, are entitlements states must pay for. Other services, like home and community-based services (HCBS), are optional. These HCBS services will likely be cut as states reduce spending they are not required to cover.

The 4.5 million people receiving Medicaid covered home care services (HCBS) will be forced to reevaluate their care options and consider alternatives, whether that is to move family members to a nursing home or provide unpaid care in the home themselves.19 As Anita from Georgia told the National Alliance for Caregiving, “Medicaid cuts not only hurt me as a caregiver but will force my mom out of her home and into a nursing home.”20

Another possibility is that adults who need some care but not institutional care, or who prefer to remain at home, may go without the support they need. Having a smaller proportion of Medicaid spending on HCBS care will result in more adults with unmet care needs.21

Reductions in the Medicaid provider tax limit will likely lead states to cut reimbursement rates to providers. Research shows that cutting reimbursement rates lowers care quality.22 Service providers, like nursing homes, adjust by cutting costs or reducing services. For example, 58% of nursing homes said they would reduce staffing levels in response to lower Medicaid reimbursement rates.23

Cuts to staffing and quality of services is bad news. Lower staffing rates in nursing homes are associated with higher use of sedatives, increased likelihood of pressure sores, increased urinary tract infections, more hospitalizations, and more emergency room visits.24 Reduced reimbursement rates also means less money to pay home care workers in a landscape where there are already significant labor shortages.25 Thus, cuts in federal funding for Medicaid will have direct impacts not only for the types of services older Americans can rely on, but also on the quality of those care services.

Care Gaps Widen as Families Shoulder Increasing Costs

When coverage and home care services are cut, unpaid family caregivers are forced to fill the gap. In states with lower Medicaid spending on long-term services and supports (LTSS), unpaid family caregivers provide more care hours.26 But unpaid caregiving comes with costs. Evidence shows that unpaid caregiving reduces caregivers’ labor force participation and work hours, and consequently, lowers lifetime incomes and reduces retirement security for caregivers.27 With the OBBB, Congress has shifted even more responsibility onto unpaid caregivers, who already provide the bulk of care without adequate support.

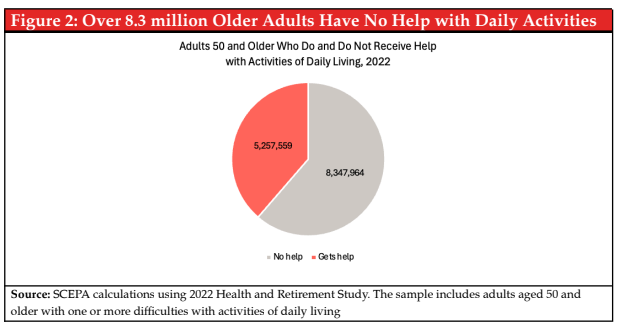

Figure 2: Over 8.3 million Older Adults Have No Help with Daily Activities

Source: SCEPA calculations using 2022 Health and Retirement Study. The sample includes adults aged 50 and older. Having functional limitations is defined as having difficulty with one or more activities of daily living.

Not all elders have family members they can turn to. For example, single adults without adult children often go with unmet care needs.28 In 2022, about 11% of adults aged 50-64 and 13% of adults aged 65+ with functional limitations on Medicaid were single with no living children. In 2022, over three out of five adults aged 50 and older with functional limitations received no help (see Figure 2)29 That share will likely increase when the OBBB’s Medicaid cuts take effect in 2026.

We Need More, Not Less, Public Investment In Care

The OBBB slashes Medicaid’s ability to support long-term care when more Americans than ever need this care. By reducing federal funding and increasing bureaucratic barriers to access, Medicaid cuts threaten to dismantle one of the few public supports available to aging Americans and their families. Ensuring that older adults can age with dignity will require reversing these changes by expanding Medicaid support and making it easier – not harder – for people to access the care they need. Congress and the president need to:

- Reverse the Medicaid cuts in the “One Big Beautiful Bill” to undo harms to a system already under strain. Congress should repeal the OBBB’s funding reductions, work requirements, and administrative restrictions that weaken Medicaid’s long-term care support.

- Increase public investments in long-term care, including:

○ Increasing access to Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) under Medicaid which ensures that adults are able to age with dignity in their homes and communities.

○ Making HCBS an entitlement rather than an optional service states can cut so that older Americans are able to stay in their homes.

○ Reducing administrative burdens to access Medicaid long-term support and services (LTSS) by using existing data sources to verify eligibility, simplifying and making online services more accessible, and adequately staffing Medicaid offices.30 Streamlined systems mean more consistent care, fewer gaps in coverage, and less stress for overburdened caregivers and administrators.

References

1. Chidambaram, P., & Burns, A. (2024). 10 Things About Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS). KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-about-long-term-services-and-supports-ltss/

2. Euhus, R., Williams, E., Burns, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2025). Allocating CBO’s estimates of federal Medicaid spending reductions across the states: Enacted reconciliation package. KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/allocating-cbos-estimates-of-federal-medicaid-spending-reductions-across-the-states-enacted-reconciliation-package/

3. Snow, M. (2025). When Will Changes to SNAP and Medicaid Take Effect? AARP.

https://www.aarp.org/advocacy/snap-medicaid-changes-timeline.html

4. Cost of Care Survey 2024: Median Cost Data Tables. (2025). GenWorth | Care Scout. https://pro.genworth.com/riiproweb/productinfo/pdf/282102.pdf

5. Johnson, R. W., & Dey, J. (2022). Long-Term Services and Supports for Older Americans: Risks and Financing, 2022 [Research Brief]. ASPE.

https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/ltss-older-americans-risks-financing-2022

6. Caregiving in the US 2025. (2025). AARP & National Alliance for Caregiving.

https://www.aarp.org/pri/topics/ltss/family-caregiving/caregiving-in-the-us-2025/

7. Colello, K. J., & Sorenson, I. (2023). Who Pays for Long-Term Services and Supports? (In Focus No. IF10343). Congressional Research Survey.

https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF10343

8. Chidambaram, P., & Burns, A. (2024). 10 Things About Long-Term Services and Supports (LTSS). KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-about-long-term-services-and-supports-ltss/

Rhee, N. (2025). Medicaid Cuts—Including Work Documentation Requirements—Harm Older Adults. UC Berkeley Labor Center.

https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/medicaid-cuts-including-work-documentation-requirements-harm-older-adults/

9. Author’s calculation using the 2022 Health and Retirement Study. “Functional limitations” is defined as having difficulty with one or more activities of daily living (ADL).

10. Mason, B. (2025, July 15). State impacts of the “one big beautiful bill.” NACHC.

https://www.nachc.org/state-impacts-of-the-one-big-beautiful-bill/

11. Rudowitz, R., Musumeci, M., & Hall, C. (2019). February State Data for Medicaid Work Requirements in Arkansas [Issue Brief]. KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-data-for-medicaid-work-requirements-in-arkansas/

12. Karpman, M., & Gangopadhyaya, A. (2025, April 23). New Evidence Confirms Arkansas’s Medicaid Work Requirement Did Not Boost Employment [Urban Institute]. Urban Wire.

https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/new-evidence-confirms-arkansas-medicaid-work-requirement-did-not-boost-employment

13. Sommers, B. D., Chen, L., Blendon, R. J., Orav, E. J., & Epstein, A. M. (2020). Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas: Two-year impacts on coverage, employment, and affordability of care. Health Affairs, 39(9), 1522–1530.

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00538;

Harker, L. (2023). Pain But No Gain: Arkansas’ Failed Medicaid Work-Reporting Requirements Should Not Be a Model. CBPP.

https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/pain-but-no-gain-arkansas-failed-medicaid-work-reporting-requirements-should-not-be

Lukens, G., & Zhang, E. (2025). Medicaid Work Requirements Could Put 36 Million People at Risk of Losing Health Coverage. CBPP.

https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-work-requirements-could-put-36-million-people-at-risk-of-losing-health

14. Hulver, S., Burns, A., & Mathers, J. (2025). Reconciliation Language Could Lead To Cuts in Medicaid State-Directed Payments to Hospitals and Nursing Facilities. KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/reconciliation-language-could-lead-to-cuts-in-medicaid-state-directed-payments-to-hospitals-and-nursing-facilities/

15. Ortaliza, J., McGough, M., Cox, C., Pestaina, K., Rudowitz, R., & Burns, A. (2025). How Will the One Big Beautiful Bill Act Affect the ACA, Medicaid, and the Uninsured Rate? (Medicaid Watch). KFF.

https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/how-will-the-2025-budget-reconciliation-affect-the-aca-medicaid-and-the-uninsured-rate/

16. Cutler-Tran, D. (2023, March 10). Medicaid Agency Workforce Challenges and Unwinding. National Association of Medicaid Directors.

https://medicaiddirectors.org/resource/medicaid-agency-workforce-challenges-and-unwinding/

17. Under the Medicaid provider tax, states are able to tax health care providers, like nursing homes, and then use that revenue to draw additional federal matching funds. These taxes are then typically recycled back to providers through higher Medicaid payments, effectively increasing total Medicaid funding without increasing state outlays. However, federal law imposes limits on how large these taxes can be. When these limits are tightened or capped, states face decreased federal funding for Medicaid, leading to potential budget shortfalls. See Kliff, S., & Sanger-Katz, M. (2025, June 17). The Senate Wants Billions More in Medicaid Cuts, Pinching States and Infuriating Hospitals. New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/17/upshot/medicaid-cuts-republicans-senate.html for a more detailed accessible explanation.

18. Euhus, R., Williams, E., Burns, A., & Rudowitz, R. (2025). Allocating CBO’s estimates of federal Medicaid spending reductions across the states: Enacted reconciliation package. KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/allocating-cbos-estimates-of-federal-medicaid-spending-reductions-across-the-states-enacted-reconciliation-package/

19. Mohamed, M., Burns, A., & Watts, M. O. (2025). What is Medicaid Home Care (HCBS)? KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/what-is-medicaid-home-care-hcbs/

20. Medicaid Enrollment and Expenditure Impacts for States Facing a Caregiving Crisis. (2025). [Fact Sheet]. National Alliance for Caregiving.

https://www.caregiving.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Crisis-States_Medicaid-Fact-Sheet_NAC_July-2025-2.pdf

21. Cheng, Z., Lee, H. B., Maeng, D. D., Hill, E. L., & Li, Y. (2025). Has increased medicaid spending on home- and community-based services reduced unmet needs in activities of daily living care among community-dwelling older adults with dementia? Evidence from 2008 to 2020. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 26(8), 105691.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2025.105691

22. Choi, J. L., Lepore, M., Trinkoff, A. M., Cooke, C. E., & PhDe, T. J. M., II,. (2025). The Effect of Medicaid Managed Long-Term Services and Supports Spending on Nursing Home Care Quality in the United States. Journal of the Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medical Association https://www.jamda.com/article/

Bowblis, J. R., & Applebaum, R. (2017). How does medicaid reimbursement impact nursing home quality? The effects of small anticipatory changes. Health Services Research, 52(5), 1729–1748.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12553; McKnight, R. (2006). Home care reimbursement, long-term care utilization, and health outcomes. Journal of Public Economics, 90(1–2), 293–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.11.006

23. New survey highlights devastating impact of medicaid reductions on nursing homes. (2025, June 9). American Health Care Association.

https://www.ahcancal.org/News-and-Communications/Press-Releases/Pages/New-Survey-Highlights-Devastating-Impact-of-Medicaid-Reductions-on-Nursing-Homes.aspx

24. Moon, K., Park, M., & Lim, J. M. (2025). First, do no harm: Do staffing shortages drive abuse and malfeasance in U.S. Nursing homes? https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5291600; Konetzka, R. T., Stearns, S. C., & Park, J. (2008). The staffing–outcomes relationship in nursing homes. Health Services Research, 43(3), 1025–1042. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00803.x; Mukamel, D. B., Saliba, D., Ladd, H., & Konetzka, R. T. (2024). The relationship between nursing home staffing and health outcomes revisited. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 25(8), 105081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2024.105081

25. Burns, A., Mohamed, M., Chidambaram, P., Wolk, A., & Watts, M. O. (2025). Payment Rates for Medicaid Home Care: States’ Responses to Workforce Challenges [Issue Brief]. KFF.

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/payment-rates-for-medicaid-home-care-states-responses-to-workforce-challenges/

26. Mellgard, G., Ankuda, C., Rahman, O.-K., & Kelley, A. (2022). Examining variation in state spending on medicaid long-term services and supports for older adults. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 41(1), 54–64.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2021.2004286

27. Maestas, N., Messel, M., & Truskinovsky, Y. (2023). Caregiving and labor supply: New evidence from administrative data (No. w31450; p. w31450). National Bureau of Economic Research.

https://doi.org/10.3386/w31450;

Butrica, B., & Karamcheva, N. (2015). The Impact of Informal Caregiving on Older Adults’ Labor Supply and Economic Resources. Urban Institute.

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/impact-informal-caregiving-older-adults-laborsupply-and-economic-resources

Van Houtven, C. H., Coe, N. B., & Skira, M. M. (2013). The effect of informal care on work and wages. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 240–252.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.006;

Wakabayashi, C., & Donato, K. M. (2006). Does caregiving increase poverty among women in later life? Evidence from the health and retirement survey. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(3), 258–274.

https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650604700305

28. Forden, J., & Ghilarducci, T. (2023). U.S. Caregiving System Leaves Significant Unmet Needs Among Aging Adults (Policy Note Series). Schwartz Center for Economic Policy Analysis at The New School for Social Research.

https://www.economicpolicyresearch.org/research/u-s-caregiving-system-leaves-significant-unmet-needs-among-aging-adults

29. Author’s calculations using 2022 Health and Retirement Study data. “Functional limitations” is defined as having difficulty with one or more activities of daily living (ADLs).

30. Wikle, S., Wagner, J., Erzouki, F., & Sullivan, J. (2022). States Can Reduce Medicaid’s Administrative Burdens to Advance Health and Racial Equity. CBPP.

https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/states-can-reduce-medicaids-administrative-burdens-to-advance-health-and-racial